Hate Violence, Fierce Love: Histories of Grief, Rage & Resistance

(from a plenary speech delivered at the Shepard Symposium on Social Justice, University of Wyoming, 2009 )

…But before we turn to the harshness and heart break of hate violence, let me begin by invoking fierce love. I don’t mean the kind of love you’re likely to find in Hallmark cards, full of platitudes and clichés. I don’t mean easy, simple, or romantic love, but rather a fierce and determined love that won’t back down, demands justice, and lives in community, a love often expressed in mundane, everyday acts.

Here’s a story about those kinds of acts. Not so long ago my good friend Deirdre visited her childhood home in suburban Long Island outside of New York City. In an unplanned turn of events, she ended up visiting her high school. At first she wasn’t going to even walk into the building. She sat in the parking lot remembering her teenage years, how she had absorbed the messages of homophobia through her skin, remembering not being safe enough to come out as a lesbian until way after graduation, still feeling that fear and isolation 16 years later. But after sitting there for a while, Deirdre decided to go inside anyway. Taped to the font door was a poster about Matt Shepard, telling the story of his life and death, describing the need to end homophobic hate violence and create safety, tolerance, acceptance, respect for LGBT people. She noticed that the hallways, the walls, the floors, the lockers looked exactly as they had when she was a student. She noticed that no one had scribbled graffiti on that poster, no one had defaced it in any way. She noticed her surprise, disbelief, relief, gratitude for Matt’s picture hanging there.

This is such the story of small acts that had consequences no one could predict. Really it’s a trail of acts from the efforts here in Laramie in the months and years since Matt’s murder to all the things that created the climate where students could finally tape that poster to the main entrance to their high school, speaking the reality of homophobic violence out loud in public. This is such a story of the legacy of change over time—from 1992 when Deidre graduated, a hurt and isolated queer white girl, to 1998 when Matt was killed to now; the legacy of change across space—from Laramie to Long Island. Fierce and determined love lives in these small acts. Fierce and determined love means remembering and grieving, means outrage, means resistance. I want us to hang on to the reality and potential of this love as we think hard and feel deeply about hate violence.

I want to talk today about three aspects of hate violence. The first is how it doesn’t fit into nice neat boxes. The second is how we need to define it in expansive terms. And the third is how it isn’t only a dynamic between individuals but often involves institutions.

First, hate violence doesn’t fit into nice neat boxes. This seems obvious enough; after all hate violence is always messy, ugly, wrenching, often confusing to sort out who did what, when. But still activists are often quick to categorize hate violence, to link acts of bullying, harassment, ridicule, abuse, assault, or murder to a single system of oppression, to name it definitively homophobic or racist, sexist or ableist, classist or transphobic. There is so much power in naming the violence prompted by the various systems that confine and shape the lives of marginalized people. And yet in the messiness of this world, hate violence often resists singular categories.

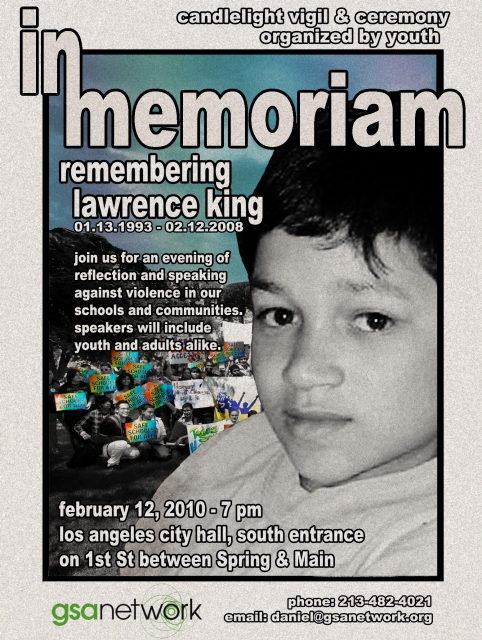

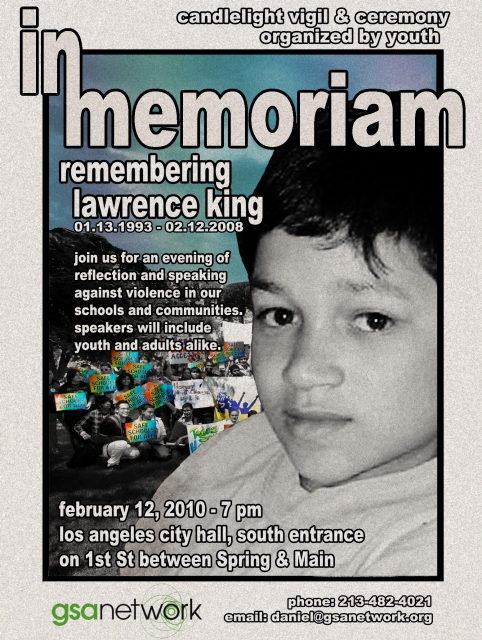

Larry’s murder has been named an act of homophobic violence, and certainly I wouldn’t disagree, but there’s more to the story. Larry wasn’t just a gay kid, a gender-exploring kid. He was also kid of color living in the foster care system, a 15-year-old in eighth grade, dealing with a learning disability.

So many rules confined his life. I wouldn’t hazard a guess as to why he was first bullied: was it because he was disabled or because he was Latinx or because he was gay or because he was poor and gender nonconforming? We lose so much if we turn Larry’s life and death into a story simply about homophobia. If we don’t understand how ableism, racism, poverty, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia tangle together to motivate violence, we will never be able to end it. We will only be able to tape mere band-aids on gaping wounds….

copyright 2009, Eli Clare