Queer Disabled Legacies: Reading Laura Hershey’s Poems

(from a talk first given at the University at Buffalo, 2021 )

Inside my queer disabled isolation

your words have found seams, cracks,

fissures—insisting, insisting: “Remember,

you weren’t the one / who made you ashamed.”

(by Eli Clare)

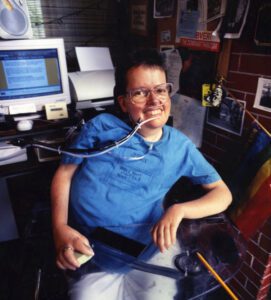

The poems of white disabled lesbian writer-activist Laura Hershey grab me, make me think about the pronoun you—the relationship between the I of the narrator and the you of the reader. In her well-known poem “You Get Proud by Practicing,” first published in the early 1990s, Laura writes directly and specifically to disabled people. There is nothing generic about the you in these prose-like lines:

“You do not need

to be able to walk, or see, or hear,

or use big, complicated words,

or do any of the things that you just can’t do

to be proud. A caseworker

cannot make you proud,

or a doctor.

You only need

more practice.

You get proud

by practicing.”

(by Laura Hershey)

Questions about pride, queerness, and disability access hover as I read Laura’s poems. I remember a conversation she and I once had about LGBTQ community. She was clear that she had found no home or resting place there. She wrote in a world shaped by the absence of ramps and elevators, which meant that all too often she couldn’t access the bars, bookstores, and many other public spaces where queer and trans communities are built. She wrote in a world shaped by endless ableist stereotypes, which meant that far too many non- disabled LGBTQ people treated her as undesirable and child-like. She named the daily grind of ableism that she encountered everywhere—and felt keenly in queer community—“the violence of stairs.” I pause to absorb the gravity of the word violence and the pun on the word stairs, referring both to an architectural feature that completely privileges walking over rolling and to the act of gawking

The absence of LGBTQ pride strikes me every time I read “You Get Proud by Practicing.” Throughout the poem, Laura focuses intently on disability pride:

“You can add your voice

all night to the voices

of a hundred and fifty others

in a circle

around a jailhouse

where your brothers and sisters are being held

for blocking buses with no lift….

You can speak your love

to a friend

without fear….

These are all ways

of getting proud.”

(by Laura Hershey)

The you is quite specific here: disability activists protesting lack of access. I could argue that the lines, “You can speak your love/to a friend/without fear,” are a veiled reference to gay/lesbian/bisexual/queer love. However, because every other image in the poem is quite straightforward, I’m not inclined to read an indirect queer meaning into these lines.

LGBTQ and disability pride are cousins, both arising from the Black Is Beautiful movement of the 1960s. Gay and lesbian activists in the early ‘70s took lessons learned from Black Power activists and created the first gay pride marches, which in turn inspired disability pride parades, starting in the 1990s and becoming more numerous in the 2000s. Laura certainly participated in a number of LGBTQ pride marches, reading at the Denver event several times and speaking at the Portland, OR event in 1999. But in writing “You Get Proud by Practicing,” she doesn’t make any moves toward twining disability and LGBTQ pride together. I’m neither calling Laura out nor suggesting that as a disabled lesbian poet she had an obligation to both kinds of pride, but I do have some wonderment about her poetic choices. She and I never had this conversation, yet I yearn toward it, trying to imagine what we might have offered each other.

Laura, I think about homophobia in the disability rights movement of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the casual assumptions of heterosexuality, how you and I navigated that terrain in such different ways. Friend, how did your navigations impact you and your poems? Did you simply lay that struggle down and decide to write about disability separate and distinct from queerness? Or did LGBTQ pride so inform what you understood about resisting shame that you just let it settle matter-of-factly into the background? I think too of the “violence of stairs” in LGBTQ communities, both then and now, and feel piercing anger, sadness, betrayal. I feel all of what pushed many of us—including you and me—to organize and make community among queer disabled people.

copyright 2019, Eli Clare